The Role of Amplification and Active Imagination within Emily Carr’s Works

“The scarlet of the maples can shake me like a cry

Of bugles going by.

And my lonely spirit thrills

To see the frosty asters like a smoke upon the hills.”

The second verse of Bliss Carman’s poem “A Vagabond’s Song” has always struck me regarding the gorgeous colours of autumn, and how our spirits cannot help but respond to Nature’s every-changing scenery. Trees, since the dawn of man’s memory, have played a large part in human civilization, progress, culture, providing a metaphor not only for the known (protection and shelter) but also the unknown (the looming unexplored territory). As such, trees have become symbols for the cycle of life and death, growth, the self, and the cosmos. Surrounded by trees, it is no wonder that Canadian writers like Bliss Carman and artists like Emily Carr drew upon their image to evoke different views on the human experience. Utilizing Jungian analytical theory and looking at McNiff’s adaptation of Jung’s amplification and “active imagination” concepts, we can see how Emily Carr’s repeated artistic motifs of trees (and by extension, totem poles) in her paintings speak to a dialogue with symbols as she came to grips with difficulties and obstacles in her life and others’ lives about her.

Emily Carr’s Biography

Emily Carr (1871-1945) is one of Canada’s foremost female painters, especially during her time. After studying art and painting at the California School of Design, Emily Carr returned to Victoria, BC worked on her art while teaching. Between 1899 and 1905, Carr spent time in England, mostly ill, returning to Canada in 1905. However, five years later, dissatisfied with her artistic knowledge and abilities, Carr decided to visit Europe, where she researched modernist art in Paris. As a result of her studies, Carr adopted a personal style in post-impressionism.

Returning to Canada in 1912, she tried to make headway as an artist, focusing on recording totem poles along the West coast of BC before they were taken down; however, Carr was not noticed for her artistic work. Unable to make enough income and now rather depressed, Carr returned to Victoria, BC and lived simply. Not until 1927 was her artwork brought to the attention of the National Gallery of Ottawa, which was putting on a show called “West Coast Aboriginal Art Exhibit”. Invited to go to Ottawa and show her art, Emily Carr could finally showcase her works as well as meet other famous artists, especially the Group of Seven – Lawren Harris, in particular. With her ambition renewed, Carr returned home and produced more art under the mentorship of her good friend Harris.

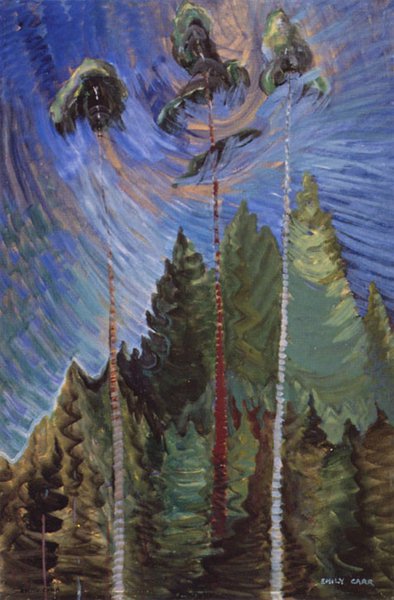

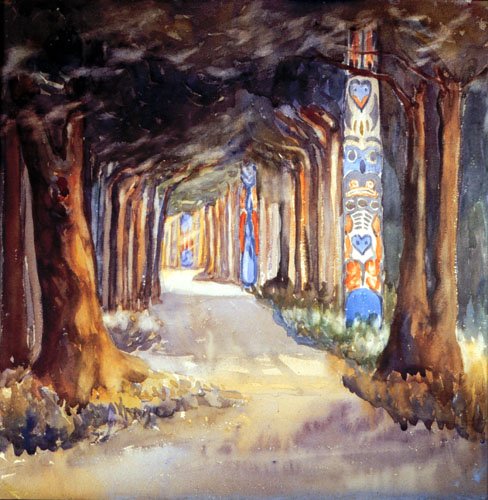

However, despite her works’ exposure and receiving more sales for her work, Carr never made much money. After her heart attack in 1937, Carr’s work output slowed down, and she focused on writing, such as Klee Wyck (Historica Canada, 2018). Emily Carr’s works, which I will be analyzing, include: Totem Walk at Sitka (1917); Scorned as Timber, Beloved of the Sky (1935); and Forest (c.1940 (The Art History Archive, 2018). Emily Carr’s main two themes are the depiction of West Coast’s landscape – nature and Aboriginal culture – with an occasional (and additional) focus of how European culture affects these spaces. As the only prolific and high-profile female painter of her time, Emily Carr’s influence remains a major factor in Canadian culture today (Canadian Art, 2018).

Jungian Theory and “The Tree”

One of Emily Carr’s favourite art motifs was the tree and the totem pole, which, when considering Jungian symbology, provides an interesting insight into what ideas Carr may have been exploring as an artist, a woman, and a Canadian.

In Man and His Symbols, Jung defines a symbol as “a term, a name, or even a picture that may be familiar in daily life, yet that possesses specific connotations in addition to its conventional and obvious meaning. It implies something vague, unknown, or hidden from us” (20). With reference to the “unknown” or the “hidden”, Jung refers to the way our unconscious works through symbols in order to come to our awareness (23). Suggesting that symbol-filled dreams become a way for the unconscious to work through submerged experiences (28), Jung argued that these instances of dreams/fantasies are a healthy way for the mind to carry subliminal messages from the instinctual mind to the rational mind (52). Symbols, holding multiple meanings, may often refer to an archetype. Archetypes, according to Jung, are “primordial images” which have a “tendency to form such representations of a motif – representations that can vary a great deal in detail without losing their basic pattern” and are therefore an “instinctive trend” found in fantasies and symbolic images (68).

Due to Jung’s theories on the importance of using symbols to “interpret” fantasies/dreams, of allowing the unconscious to manifest archetypes, and of recording these dreams/fantasies, many psychotherapists have researched symbols. Trees are an important image, symbolizing the cosmos, the self, and the cycle of life and death. According to Cirlot, plants are “an image of life” and a “manifestation of the cosmos and of the birth of forms”, linking to “the mystery of death and the resurrection” (A Dictionary of Symbols, 259). “One of the most essential of traditional symbols”, trees denote “the life of the cosmos: its consistence, growth, proliferation, generative and regenerative processes” (346-347). Similar to mountains and ladders, trees can also represent upward trends (347). The meaning for the “tree-symbol” proliferates, but the general idea behind “the tree” is one of growth and renewal.

Taking these symbols and archetypes into account, Jung theorized psychotherapy concepts such as amplification and active imagination techniques. Amplification is a way to interpret dreams, originally, created by Jung. The image is interpreted two ways: through the universal symbology known to the therapist (objective amplification) and through personal interpretation (subjective amplification). Active imagination is a technique used in subjective amplification whereby the client finds personal associations with the symbol and, finds healing through the release of the creative in dreams, fantasy, and art (Malchiodi, 67-68). Jung’s theories, based on symbol and archetype, consequently lent themselves well to the approaches of image-based art therapy.

McNiff’s Integration of Jungian Amplification and Active Imagination

According to Malchiodi, McNiff adapted Jung’s active imagination process, creating his own style which he called “dialoguing with the image” (69). McNiff’s approach hopes to “consider images in a nonreductive way”, allowing the client and image to transform over time. In his book Art Heals: How Creativity Cures the Soul, McNiff states that:

“It is imperative to liberate images from ourselves, give them more creative autonomy, and restore the reality of imagination as a procreative and life-enhancing function. If we can step out of our self-referential psychologies for a moment and imagine our dreams, pictures, poems, dramas, music, and movements as partners, a new basis will be established for therapeutic ethics and methods” (100-101).

McNiff recommends inviting images to visit us – and allowing them to speak (102-103). He likens artistic expression to “offspring, and like children they are related to but separate from their makers” (106). By seeing art as living and speaking, the art therapist and client can then remove themselves from positions of power over the image and thus allow the meaning of the image to shift (107). Art and the integration of the symbol is thus more “an archetypal and protean process rather than the tidy chain of individual human inventions and direct influences” (108).

On a more practical level, McNiff develops his concept of “dialoguing with the image” as involving actual conversations with the painting (108). Talking to the painting (and waiting for an answer) as if it were a person not only allows for meditation, but also encourages active thinking. McNiff argues that “talking is a form of thinking in which thoughts take shape through the interaction of participants” (109). “Dialoguing with the image” also involves reading the painting on a personal and relative basis, allowing for shifts in meaning. In this way, the therapist and client move from reliance on symbology alone to more personal ownership.

Dialoguing with Emily Carr’s Trees

Considering how personal McNiff’s approach is to art therapy, reading Emily Carr’s tree paintings becomes complicated. We as art viewers are unable to understand Carr’s journey in its entirety, yet we may make some guesses by taking into consideration her own writings on life and nature. Within her writing, we can see how Carr was constantly in “dialogue with the images” of her painting – and the world from which she drew inspiration. In her now published journal Hundreds and Thousands: The Journals of Emily Carr, Carr wrote:

“Go into the woods alone, and look at the earth crowded with growth, new and old bursting from their strong roots hidden in the silent, live ground, each seed according to its own kind expanding, bursting, pushing its way upward toward the light and air, each one knowing what to do, each one demanding its own rights on the earth. Feel this growth, the surging upward, the expansion, the pulsing life” (Newton, 2017).

Symbolically, then, the tree represented for Carr what it has represented for many – growth and renewal. They also represent a struggle to survive and thrive – in the same way Carr herself struggled to be recognized as an artist.

Although other paintings such as Tree Trunk (1931) and Old Tree at Dusk (1936) focus more closely on the trunks of the trees, looking at Totem Walk at Sitka (Carr, 1917), Scorned as Timber, Beloved of the Sky (1935), and Forest (1940), we can see how trees are depicted when viewed in their entirety: tall, sinuous, ephemeral, and colourful (see Appendix A for a coloured gallery of Carr’s works). Therefore, we can see not only in Carr’s journals but also in her paintings, how the upward reach of trees, accompanied by struggle and threatened by humanity, represents God (and positive forces) in the arts, in the art, and in life. As she wrote in her journal, “Go out there into the glory of the woods. See God in every particular of them expressing glory and strength and power, tenderness and protection. Know that they are God expressing God made manifest” (Carr, 2009).

McNiff’s form of amplification and active imagination may not allow for us to make definitive interpretations of Carr’s artwork, but we can see how Carr’s return to the tree-symbol – and the totem pole – may reveal her concern about the increasing loss of Aboriginal culture within the rapidly changing cultural landscape of Canada. In fact, in Totem Walk at Sitka (Carr, 1917), we can see how easily the totem poles fit within the framework of trees, being an organic incorporation of the human in nature, but like trees, totem poles are in danger of being cut down. Furthermore, in her article Tree as self symbol, Levesque, a French art therapist, suggests “three dimensions represented in trees; crown: conscious personality or opportunities for expression, trunk: self-esteem, desire for self-expansion and roots reflected how someone was ‘rooted’ in life. The trunk can be the person’s experience of the body and the branches how one reaches out and gather’s ‘light’ which can symbolise how one relates and perhaps reaches out to other people” (Levesque, 2018). In her journal, Carr touches on this concern often, writing:

“I am always asking myself the question, What is it you are struggling for? What is the vital thing the woods contain, possess, that you want? Why do you go back and back to the woods unsatisfied, longing to express something that is there and not able to find it? […] Only by right living and a right attitude towards my fellow man, only by intense striving to get in touch, in tune with, the Infinite, shall I find that deep thing hidden there…” (Carr, 2009).

Therefore, I would argue that Carr subconsciously used the tree motif over and over in order to draw on the symbolic power of renewal and unity for herself and the Aboriginal people of BC as found within the tree archetype. As McNiff suggested for better art therapy practices, Carr interacted with her subject matter (trees) and the paintings they inspired – and the results can be seen within her journaled outpourings.

Conclusion

Carr’s trees are not monolithic. Just like people, each of her trees contain character and difference. Each represent a different moment in Carr’s life. Although we cannot definitively define what trees meant at anytime to Carr, we understand from the stylistic approach to her trees as well as her journals that trees represented a source for “the Infinite” from which she gained peace, confidence, and hope for the future. Like Bliss Carman, Carr represents the artist who finds healing within nature.

“There is something in October sets the gypsy blood astir;

We must rise and follow her,

When from every hill of flame

She calls and calls each vagabond by name.”

Bibliography

Carman, B. (1919). “A Vagabond’s Song”. Modern American Poetry. (L. Untermeyer, Ed.) Retrieved March 9, 2018, from Bartleby: http://www.bartleby.com/104/24.html

Carr, E. (1917). Totem Walk at Sitka. Retrieved March 7, 2018, from http://www.arthistoryarchive.com/arthistory/canadian/images/EmilyCarr-Totem-Walk-At-Sitka-1917.jpg

Carr, E. (1931). Tree Trunk. Retrieved March 7, 2018, from http://www.arthistoryarchive.com/arthistory/canadian/images/EmilyCarr-Tree-Trunk-c1931.jpg

Carr, E. (1935). Scorned as Timber, Beloved of the Sky. Retrieved from http://www.arthistoryarchive.com/arthistory/canadian/images/EmilyCarr-Scorned-as-Timber-Beloved-of-the-Sky-1935.jpg

Carr, E. (1936). Old Tree at Dusk. Retrieved March 7, 2018, from http://www.arthistoryarchive.com/arthistory/canadian/images/EmilyCarr-Old-Tree-at-Dusk-c1936.jpg

Carr, E. (1940). Forest. Retrieved March 7, 2018, from http://www.arthistoryarchive.com/arthistory/canadian/images/EmilyCarr-Forest-c1940.jpg

Carr, E. (1942). Cedar Sanctuary. Retrieved March 7, 2018, from

Carr, E. (2009). Hundreds and Thousands: The Journals of Emily Carr. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre Publishers.

Carr, E. (n.d.). Odds and Ends. Retrieved March 7, 2018, from http://www.arthistoryarchive.com/arthistory/canadian/images/EmilyCarr-Odds-and-Ends-DateUnknown.jpg

Cirlot, J. E. (1962). A Dictionary of Symbols. (J. Sage, Trans.) New York: Philosophical Library.

“Emily Carr”. (2018). Retrieved March 7, 2018, from The Art History Archive: http://www.arthistoryarchive.com/arthistory/canadian/Emily-Carr.html

“Emily Carr”. (2018). Retrieved March 7, 2018, from Historica Canada: http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/emily-carr/

“Emily Carr”. (2018). Retrieved March 7, 2018, from Canadian Art: https://canadianart.ca/artists/emily-carr/

Jung, C. G., Henderson, J. L., von Franz, M. L., Jacobi, J., & Jaffe, A. (1964). Man and His Symbols. London: Doubleday.

Levesque, F. (2018). Tree as self symbol. Retrieved March 8, 2018, from Douglas Institute: http://blog.douglas.qc.ca/arts/2009/10/09/tree-as-self/

Malchiodi, C. A. (2012). Chapter 5: Psychoanalytic, Analytic, and Object Relations Approaches. In C. A. Malchiodi (Ed.), Handbook of Art Therapy (2nd ed., pp. 57-74). New York: Guilford Press.

McNiff, S. (2004). Art Heals: How Creativity Cures the Soul. Shambhala.

Newton, E. (2017, July 7). Emily Carr in the Forest. Retrieved March 11, 2018, from Creators Vancouver: http://creatorsvancouver.com/emily-carr-in-the-forest/

Ronnberg, A. (2017). Introduction. Retrieved March 7, 2018, from The Archive for Research in Archetypal Symbolism: http://aras.org/documents/more-research-aras-world-tree